Gingko

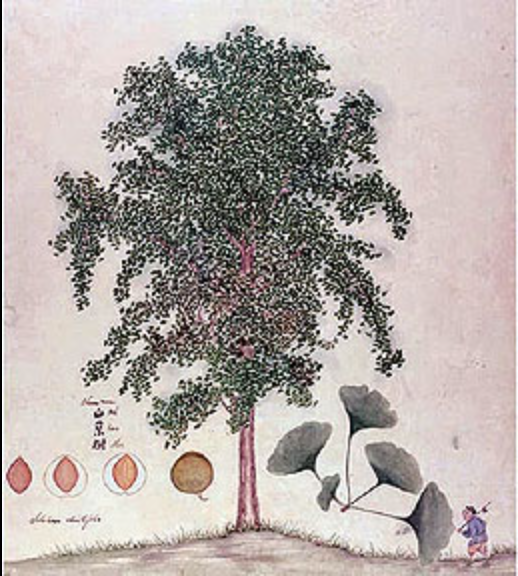

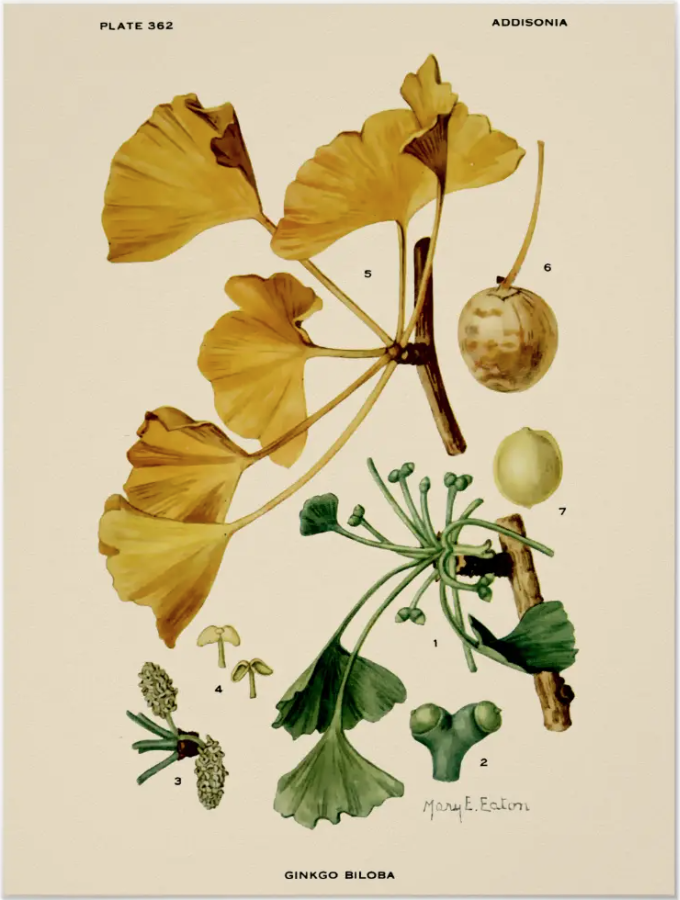

Names Ginkgo/Gingko biloba, biloba means two-lobed, also called maidenhair tree because it looks similar to the maidenhair fern, Chinese names: white fruit (bai guo), silver apricot (yin xing), duck foot. Spelled both gingko and ginkgo.

Family: “Amazingly, it is the only member of its genus (Ginkgo), which is the only genus in its family (Ginkgoaceae), which is the only family in its order (Ginkgoales), which is the only order in its subclass (Ginkgoidae). The tree is also the only living connection between ferns and conifers. Phylum: Ginkgophyta. A nonflowering Gymnosperm.

In my garden's care and favour

From the East this tree's leaf shows

Secret sense for us to savour

And uplifts the one who knows.

Is it but one being single

Which as same itself divides?

Are there two which choose to mingle

So that each as one now hides?

As the answer to such question

I have found a sense that's true:

Is it not my songs' suggestion

That I'm one and also two?

-Goethe

Gingko’s History and Habitat

Gingko is a symbol of endurance and vitality as one of the oldest trees, having lived 270 million years ago in the time of the dinosaurs. Its age aligns to when sharks came into existence. It lost its habitat due to climate change. Fossil records show gingko had a more wide spread habitat, with many species in North America. By the time there’s evidence of people cultivating gingko in China, the gingko tree was close to extinction.

In the 1700s Westerners discovered these trees in a Chinese monastery where the monks had been tending them for generations. After this discovery, gingko caught fire in popularity for its beauty, adaptability, and nutritious nuts. It’s unique to have only one entry for a genus, order, and subclass, and all modern gingkoes are related to the gingkoes that were cultivated in China. Gingko is truly a survivor tree.

In Asian culture, gingkoes have long been a symbol of strength, peace, and hope, and this symbolism was amplified after Japanese gingkoes survived both the 1923 Kanto earthquake and the 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima. At Hiromshima, some gingkoes were less than two miles from the epicenter, and miraculously made a full recovery, solidifying its association not only with strength and endurance, but also resilience.

In Chinese culture, the two-lobed leaves are associated with the duality (and unity) of yin and yang, light and dark. The wind pollinated trees are dioecious, meaning they are either male or female. Only the female trees bear fruit and that fruit has a reputation for being stinky, perhaps only in repulsive competition with durian fruit. The stink is from butyric acid, named for its presence in rancid butter, and the smell is often commented to be rancid, putrid, or like vomit.

Gingko Fruit

Gingko is also very successful as there’s no way to discern which sex the trees are until they are mature enough to fruit between the ages of 20 and 30 years old, which has ensured that the female trees are planted as often as the males. In the fall, it’s possible to find gingkoes by nose before sight as the fruits are so strongly scented. They’re popular urban street trees, because of their adaptability and toughness, tolerant of adverse conditions like wind, pollution, and fire, and they produce chemicals that deter insects.

Traditional Use and Properties of Gingko Nuts

Traditional use of gingko was with its nuts, technically the seeds of the fruit, but almost always referred to as gingko nuts. Handling the fruits can cause a rash in one in fifty people, that some compare to poison ivy, due to anacardic acid, so handle nuts and forage wearing protective gloves. In NYC enough gingko nuts fall to the ground every fall that foragers sometimes claim trees as their territory, eager to gather their autumn treasures.

Gingko Fruit

Raw nuts are green and must be cooked before they’re edible. Sometimes they’re also soaked before cooking, which further reduces the toxins in the nuts besides the cooking process of baking, boiling, roasting, or steaming. Used in sweet and savory dishes, moderation is key, as gingko nuts have toxic substances, like 4′-methoxypyridoxine (MPN) and cyanogenic glycosides, that can be tolerated in small amounts but can affect individuals differently. Ginkgo oil was also used for heating and lighting.

Gingko nuts were traditionally used for skin conditions, respiratory ailments, and cavities. The 6th-century Chinese text, the Ben Cao Gang Mu by Li Shi-Zhen, references the ancient prescription of ginkgo seeds for skin infections, which has been affirmed in recent studies: “seed coats and immature seeds exhibit antibacterial activity against Gram-positive skin pathogens (C. acnes, S. aureus, and S. pyogenes).” [Another reference to this antibacterial activity.]

The Ben Cao Gang Mu has more to say about traditional Chinese use of gingko seeds:

And:

Modern Insights on Gingko Nuts

Current research has identified nine chemicals of interest in studying gingko’s potential applications: bilobalide, ginkgolide A, ginkgolic acid C15:1, ginkgolide B, isorhamnetin, quercetin, ginkgotoxin, rutin, and kaempferol. Gingko’s range of actions is wide. Gingko’s glycosides and terpenoids may have beneficial effect on neurotransmitters to improve nerve and brain health.

Gingko nuts are bitter, astringent, mildly toxic, expectorant, sedative, antitussive and have been used in to ease asthma, bladder infections, expel mucus from bronchioles and lungs, ease wheezing and coughs, stop leucorrhea and spermatorrhea, regulate urination, working on the lung and kidneys meridians in TCM (Traditional Chinese Medicine). In Chinese practice, gingko nuts are sometimes macerated in sesame oil for three months before being used. This preparation has successfully treated tuberculosis.

Gingko Leaf Use and Benefits

Though there is some evidence of traditional use of gingko leaves, their medicinal use is generally considered a modern Western development. The green leaves are too tannin-rich to be ideal compared to the autumn yellow leaves. The yellow leaves are rich in flavinoids, and their active constituents (gingko flavones and terpenes) are not water soluble, so an alcohol-based preparation (extract=tincture) is most common, with vinegar being the next best extraction solution. The leaves are a source of chromium, niacin, calcium, phosphorus, selenium, zinc iron, potassium, sodium, thiamine, and vitamin A.

There has been substantial research on the efficacy of gingko leaf extract: “GB possesses twenty-seven active compounds with multi-target synergistic actions for the therapeutic approach to neurodegenerative disorders.” Gingko is commonly used to treat blood flow issues, and age-related memory and concentration issues, valued for its circulatory (general and cerebral) and neuroprotective qualities.

Some actions of Gingko biloba leaf are:

rich in antioxidant flavinoids that protect the heart muscle and blood vessels and reduces the effect of free radicals, reduces inflammation in blood vessels, tones arteries, reduces platelet clumping

improves cerebral, respiratory, peripheral circulation

supports microcirculation in bone healing, used internally and externally in the affected area

gingko inhibits the activity of platelet-activating factors that cause inflammation present in asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and respiratory allergies

helps reduce anxiety

helps treat the inability to achieve orgasm due to antidepressant medications

free radical scavenger and “The antioxidant properties of G. biloba contribute to protecting the cardiovascular system, brain, and retina from free radical damage associated with aging.

terpenoids dilate blood vessels and improve circulation.

Contraindications

While some research questions whether there is any negative side effect of using gingko with blood thinners like Warfarin, out of caution it is highly recommended to avoid gingko with blood thinners. Additionally, “use of ginkgo in patients with bleeding disorders or those who take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiplatelet, or anticoagulant therapies requires caution.”

Signs of toxicity have been observed more with gingko nuts than leaf and include: headache, fever, tremors, irritability, labored breathing. Antidotes are gingko seed shells or licorice root. This is another reason to wear protective gloves when handling gingko nuts. Gingko leaf contraindications include headaches in some people, and on the rare end of the spectrum, bleeding of the eyes. Not recommended in children younger than 12 years old.

The oldest gingko at Kew Gardens from 1762.

Gingko is a plant that can be tolerated for a decent amount of time, but should be considered in moderate volumes for finite amounts of time for acute or chronic conditions, not to be used as freely as a tonic herb. My inclination would be to use a small dosage of gingko leaf extract for a set amount of time, take a break and evaluate, and then perhaps repeat with careful consideration.

Gingko in Prospect Park, Brooklyn

Medicine Making and Dosage Notes

The leaf extract standard is 24:1, meaning “the dry extract is pharmaceutically prepared to a 35–67:1 ratio of dried leaves to final extract; standardization is carried out to 24% ginkgo flavonol glycosides (based on flavones like quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin) and 6% terpene lactones (ginkgolides and bilobalide).”

David Winston mentions using gingko leaf extract for head trauma injuries, and in formulas to prevent glaucoma, cataracts, and diabetic retinopathy, suggesting 40-60 drops per day, or 2-3 dropperfuls.

Gail Faith Edwards notes using gingko leaf extract at 40 drops twice a day to support memory, mood, and cardiac support, with the increase of blood flow to the brain, easing anxiety, tension, and depression. For circulatory support, start with 20-30 drops per day.

Cooking Notes

Gingko nuts, with their seasonality and need for time-consuming specific procedures naturally gearing them to be a sometimes food, should not be considered an everyday food because ginkgolic acids can lead to vitamin B deficiency. The wisdom of many years of traditional preparation is affirmed by science that baking, boiling, can minimize nut toxicity. While they can promote digestion, gingko nuts can also upset the stomach, so Japanese folklore suggests eating only a few at a time. For first time gingko nut eaters, start slowly to judge your sensitivity.

The nuts are only edible after cooking. Wildman Steve Brill recommends this method: wash the nuts (in the shell), bake in shell at 275F for 25 minutes (some people boil them), cool the nuts, crack the shells and extract the nuts. They are called “nuts” but the seeds’ texture is softer, more like a chestnut, than hard like a walnut. Use gingko nuts as a snack food, in appetizers or entrees. They are often mixed with ingredients like rice, tofu, stir fry veggies, and mushrooms. Gingko nuts will dry out in the refrigerator, so freeze cooked nuts and rebake for a short time to restore the texture after being frozen.

Gingko in Art

This “something old” has been discovered again and again from an aesthetic pleasure point of view and has been a subject in art in many mediums, from painting to pottery to metalwork and jewelry to architecture. How beautiful it would be to fully explore gingko biloba in art, though it would be a vast undertaking.

Art Nouveau façade of Prague’s Hotel Central, featuring ginkgo leaves & seeds

a stylized gingko leaf is Tokyo City's symbol

Gingko is visually important, especially in China, and in Japan. Gingko was brought to Japan from China around 1400 according to the tree ring dating of a famous thousand year old gingko at the Shinto shrine of Tsurugaoka Hachimangū in Kamakura, Japan. Today, gingko biloba is a symbol of Tokyo, the offficial tree of Tokyo, as well as the symbol of Tokyo University (two gingko leaves), the logo of Osaka University, and the symbol of one of the main schools of Japanese tea ceremony.

Subtle Healing

David Dalton’s gingko essence given to 30 people for 7 days reported that gingko supported mental clarity and calming, helped participants check in with what balance looks like in their lives bringing awareness to what is out of alignment, restore a sense of connection with the energy body, the breath, increasing right and left brain function, time and nature, restoring a sense of calm and peace.

Robin Rose Bennett mentions gingko “for journeying into the past or future, developing the gift of prophecy, retrieving ancient wisdom, rebirthing yourself, astral traveling, recalling past lives, and for clear mental focus.”

Robin Rose Bennett also writes of gingko helping to synergize the nervous system with the heart. I think then of how ginkgo can be used to support the nervous system’s alignment with the heart, and how the Chinese understanding of the heart speaks of its relationship with the gut, the nervous system, and the brain with a more holistic understanding than the general western conceptualization. In an age where so many people feel a sense of disconnection, gingko, to me, is an exciting teacher, a keeper of ancient medicine ready to be spiraled into the interconnection of now, bringing its light, patience, and strength to these transformative times.

Gingko in Prospect Park, Brooklyn

My personal experience with gingko has been relatively small. I’ve tried gingko nuts a few times, mostly prepared in restaurants. I’ve taken a wild-crafted (not standardized) extract on occasion to connect and meditate with gingko. This year on my November birthday I was drawn to visiting the gingkoes here in Brooklyn. The sheer volume of yellow gives me joy, and I love to sit with them. Even these trees, youthful and small compared to the world’s oldest gingkoes, have a combination of strength, levity, patience, and wisdom that is awe inspiring. I’m excited to learn more from gingko as a green elder, and if you have any gingko jewels from your experience, I’d love to hear from you.

Gingko in Prospect Park, Brooklyn

There are lots of stories of how when the gingko leaves drop, sometimes seemingly all at once, it’s time to celebrate, almost like a gingko holiday.